A shockingly passable Drake and the Weeknd counterfeit raises all sorts of questions about the future of artistry and listener demand

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/72202362/AImusic_getty_ringer.0.jpg)

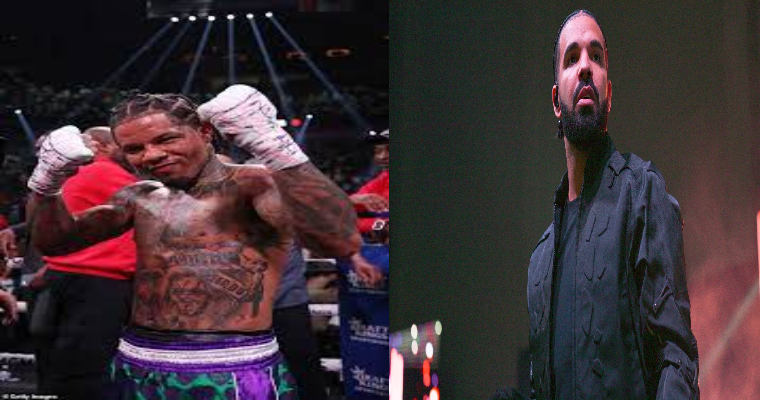

It’s been a decade since Drake and the Weeknd last performed together on a record: Drake featured on “Live For,” a single from the Weeknd’s maligned debut album, Kiss Land. As hip-hop and R&B superstars out of Toronto, Drake and the Weeknd were once close collaborators, but their careers diverged when the Weeknd signed to Republic Records and killed the joint fan base’s dream of OVOXO. So this month, it was a surprise to hear a fateful new song, “Heart on My Sleeve,” featuring Drake and the Weeknd, produced by Metro Boomin—but not really, as the song was composed by artificial intelligence.

The song’s true producer, a mysterious figure currently known only as Ghostwriter, first shared “Heart on My Sleeve” on TikTok. He’s so far withheld any explanation of how exactly he made the song, so it’s unclear whether the voice performances on “Heart on My Sleeve” were entirely generated by AI or simply modified to make the “real” performer sound like Drake and the Weeknd. (You can hear examples of both approaches in other unambiguous instances.)

It’s worth evaluating the quality of “Heart on My Sleeve” before we wrestle with the supposed cyber-dystopian implications of this sort of thing. The song is a shockingly passable counterfeit composed with a careful consideration of the artists’ personalities and tendencies. Drake and the Weeknd both play on some recent romantic drama involving Justin Bieber, Hailey Bieber, and Selena Gomez. The verses preserve some signature tics: Drake ending every one of his bars with a guttural discharge (“ay,” “yeah”) and the Weeknd initially mimicking Drake’s flow but then getting a little looser later in his verse (though my colleague Alyssa Bereznak notes some uncharacteristic sheepishness in his high notes). The beat is much less convincing though: Metro Boomin wouldn’t typically employ a piano melody in such a clunky and repetitive style.

Overall, I rate “Heart on My Sleeve” highly as a passable imitation. I rate it a bit lower, though, as a song. There’s now a cottage industry of content creators churning out their own AI impersonations of popular artists—Drake, Kanye West, Travis Scott—though none of the others I’ve encountered so far are quite as technically impressive or technologically menacing as “Heart on My Sleeve.”

The recent spike in the sophistication of artificial intelligence applications excites some people and terrifies others. Tech critics and AI skeptics have spent the past several months—ever since OpenAI launched ChatGPT in November, effectively—agonizing about the potential implications for humanity. Some of these critics are posing the big civilizational questions of postapocalyptic science fiction. What if HAL 9000? What if Skynet? Others are more concerned with the economic impact. What if the latest advances in artificial intelligence accelerate the rate of job loss due to automation? Of course, as a critic, I’m inclined to concern myself with the cultural dimension. What if artificial intelligence puts working class writers and artists out of jobs, and what if this isn’t just a labor problem but also a cultural one? What if we gradually lost the ability to distinguish between sights, sounds, and ideas produced by humans and similar content produced by software? What if “Heart on My Sleeve,” or something like it, tops the Hot 100? This feels like a point of no return.

Universal Music Group, which has Drake, the Weeknd, and Metro Boomin under recording contracts, has spent the past several days working to purge “Heart on My Sleeve” from every last corner of the internet. (That’s why the song isn’t linked here.) The company put out a remarkably charged statement imploring “all stakeholders in the music ecosystem” to declare their allegiance for either “the side of artists, fans and human creative expression, or on the side of deep fakes, fraud and denying artists their due compensation.” But you should read the statement in full. It begins with UMG conceding the role of cutting-edge technology in empowering musicians and acknowledging its own efforts to develop music-related AI. So much for the sanctity of “human creative expression”!

The music industry has been recruiting specialists and developing this sort of technology for a while. These efforts previously peaked last August with Capitol Records notoriously signing its first-of-a-kind AI rapper, FN Meka, but then dropping him in the face of backlash to the supposed racial insensitivity of his lyrics and stylization. This backlash highlighted the big blind spots for AI: cultural context for genres and biographical context for artists and songs. VTubers like Meka can do a lot—they can take on distinct personalities, and they can build fan bases from scratch, but they can’t (yet) reliably negotiate the complex racial dynamics of hip-hop, and they certainly can’t (yet) date Selena Gomez. AI is, essentially, a black box of statistics and linguistics. It can, evidently, improve its simulation of some of this stuff, but its output will likely remain a distinct subset of art and culture. Its own genre, if you will.

It’s a little too late to reverse the incorporation of computers, at the expense of more traditional instruments, into modern music, and the fearful impulse to draw some bright line at the incorporation of artificial intelligence is a little too arbitrary. The distinction between artistry and technology isn’t as stark as suggested in the more hotheaded bits of that press release from UMG. It’s more of a spectrum—though admittedly one that seems to be pushing its futuristic extreme. Some of the anxiety in this context is less about the future of music and more about the present or the past couple of decades. Someone who hates Drake, or hates trap, or hates hip-hop, or hates pop—someone who resents the computerization of modern music in general—is likely to hear “Heart on My Sleeve” as a vindication of so many curmudgeonly complaints about audio overproduction. If labels, artists, and fans were intent on diminishing the premium on natural talent, then what did we expect? If a producer equipped with fledgling software can more or less reconstitute the voices of two of the most popular artists in the world, then how good are they really, and who’s to say they shouldn’t be rivaled, if not outright replaced, by AI? Maybe we get the culture we deserve.

But it’s still a bit too early to be entirely pessimistic. Music and technology have a fraught relationship in some areas and a beautiful interaction in others. Maybe Ghostwriter just launched the annihilation of music as both art and profession, in a sure sign of darker days for humanity in the age of AI. Or maybe Ghostwriter, apparently a young musician himself, is pioneering a new genre with new tools—a tale as old as music itself.